Seven Oaks Classical School in Ellettsville received a 5-year extension to its operating charter recently. Well, not that recently. It happened in December 2022. Ellettsville and Monroe County residents may have missed it, though, because the extension was approved nearly 200 miles away.

It was approved by the three-member board of Grace Charters LLC, a nonprofit formed by Grace College and Theological Seminary to authorize charter schools, which are publicly funded and privately operated. The board met on the Grace College campus in Winona Lake, Indiana.

To meet legal requirements for public meetings, a notice was published in the local newspaper: the Warsaw Times-Union, which probably no one in Monroe County reads. One member of the public attended, according to minutes of the meeting: Seven Oaks headmaster Stephen Shipp.

The situation highlights the tension between public and private in Indiana charter schools. The Seven Oaks website says charter schools are “tuition-free, open-enrollment public schools.” But the school’s authorizer, which sets the terms of its operation and is supposed to hold it accountable, is a private, Christian college with no connection to the community where the school operates.

Seven Oaks is part of a network of charter schools aligned with Hillsdale College, a conservative and politically active private college in Michigan. The Hillsdale charter initiative once cast itself as part of a “war” to reclaim America from “100 years of progressivism” in education. Its president, Larry Arnn, led Donald Trump’s 1776 Commission and its promotion of “patriotic history.”

Grace College has also granted a charter to Valor Classical Academy, a Hillsdale-affiliated school that has stalled in its attempts to open in Hamilton or Marion County.

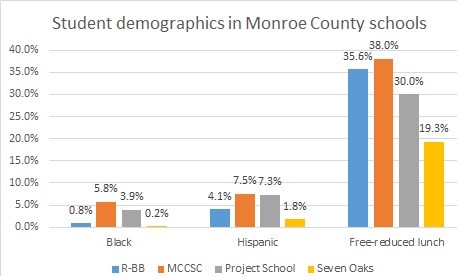

Along with the Hillsdale affiliation, there are other factors that distinguish Seven Oaks from public schools: for example, its demographic profile. Out of more than 500 students, one is Black and nine are Hispanic, according to state data. Fewer than 20% of students would qualify for free or reduced-price meals if they were provided. (The school doesn’t provide transportation or school lunches).

Nine of its 38 teachers are Hillsdale College alumni, according to profiles on the school’s website. In 2021-22, the most recent year for which a state teacher statistics report is posted, nearly 40% of its teachers had emergency licenses, compared with 4.6% in local public school districts.

The 24-page Seven Oaks charter extension reads like a standard agreement, with boilerplate language from state law and recommended practices for authorizing. It spells out the duties of each party, the expectations for the school, and the legal remedies if something goes wrong. An attached accountability plan includes out-of-date references to state assessments and, I’m told, is being revised.

The agreement says Grace College gets to keep 2.5% of the school’s state funding as an authorizer fee. That’s less than the 3% maximum that Indiana allows. In 2023-24, the college will net about $93,000.

Grace initially approved a charter for Seven Oaks in 2016 in one of Indiana’s first examples of what’s called authorizer shopping. The school’s founders applied to the Indiana Charter School Board, but it rejected their application. They reapplied but withdrew after a negative recommendation from the board’s staff. Then they took their plan to Grace College, which said yes to a 7-year charter.

At that time, private colleges could authorize charter schools in closed-door meetings with no public notice. Since 2017, they’ve had to use nonprofit authorizing agencies, such as Grace College’s Grace Charters LLC, that are subject to open-meetings and public-records laws. Even so, it can be hard to keep up. I started asking by email about the Seven Oaks charter extension in March; it took until late May to get copies of the December 2022 board minutes and the school’s extended charter agreement.

Transparency is one issue of having distant authorizers for charter schools, but there are others. The National Association Charter School Authorizers cautions against throwing the door wide open for higher education institutions, or HEIs, to authorize schools, as Indiana has done since 2011.

“While having one or two HEI authorizers may benefit the state,” it says, “the presence of too many authorizers — especially those overseeing few schools — can lead to wide variations in authorizing standards and poor achievement results for schools.”

Most of Indiana’s approximately 100 charter schools are authorized by public Ball State University, the Indiana Charter School Board or the Indianapolis mayor’s office. So far, only three private colleges have joined the game, although about 30 are eligible. Grace College authorizes four charter schools, including Seven Oaks. Calumet College of St. Joseph authorizes two.

But more charter applicants have turned recently to private Trine University in northeastern Indiana and its authorizing agency, Education One. It authorizes 11 charter schools in Indianapolis, South Bend, Fort Wayne, Gary and Bedford, with seven more slated to open by 2024. Several are expansions of the established, Indy-based Paramount, Phalen and Purdue Polytechnic charter programs.

Why are they doing this and what will be the results of this shift in authorizing? Those are questions that state education officials might want to ask.

Pingback: Indiana: Hillsdale-Style Charter Approved Remotely | Diane Ravitch's blog